By:

Gary Porter

“Just who do we think we are?” stated

Chief Justice John Roberts,

[1] in what, I predict, will no doubt become one of the most famous statements ever made in a Supreme Court dissent, barely edging out “[The Constitution] had nothing to do with [today’s decision.]”

“Petitioners make strong arguments rooted in social policy and considerations of fairness,” (emphasis added) he continues. Social policy? I thought Supreme Court decisions were to be rooted in the law? “The majority’s decision is an act of will, not legal judgment,” Roberts reminds us.

“The Celebrated Montesquieu” said: “There is no crueler tyranny than that which is perpetuated under the shield of law and in the name of justice.”

Social justice, the great utopic goal of every Progressive, not jurisprudence, was the goal of the five Justices who formed the majority opinion in Obergefel vs Hodgesl.

It was an act of judicial activism.

What do we mean by judicial activism?

The Heritage Foundation defines it this way: “

Judicial activism occurs when judges write subjective policy preferences into the law rather than apply the law impartially according to its original meaning.”

There is no better example than Obergefell.

Prior to Obergefell, the most famous statement by a

Supreme Court Justice which encapsulated the idea behind judicial activism occurred when Associate

Justice Thurgood Marshall described his judicial philosophy as: “You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.” That’s simply an amazing statement for a jurist: Ignore the law and rule instead based on your “feelings” of what is right. It’s all about feelings to a Progressive; in fact the law is often seen as an obstacle to PROGRESS. So, if you can get a court to declare its sense of justice as “the law,” instead of constraining itself to proper interpretation of the law, all the better.

But judicial activism is often in the eye of the beholder. The perfect example is Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission. The Right saw the decision as an affirmation of unrestrained free speech, the Left saw the decision as the perfect example of judicial activism since it “declared corporations were people,” as I heard more than one liberal insist.

Judicial activism is a natural outgrowth of the doctrine of legal positivism, which replaced

natural law theory in the late 1800s.

Legal Positivism holds that the only relevant law is what man creates. Natural law, if it exists at all, is irrelevant; and revealed law (i.e. as found in the Bible) has no place in a mature society. Since man is constantly evolving (so goes the theory) the law must continually evolve as well. And who guides the evolution of the law? Why, the judges, of course.

In another candid moment, Associate Justice

Ruth Bader Ginsburg wondered aloud whether the court went “too far, too fast” in its 1973

Roe v. Wade decision; yet another admission that Progressives see the Court as the “seeing eye dog” of a society groping culturally in the dark. So, perhaps the court went “a smidgen” too far in 1973; so what? Fifty million undelivered babies might have a different opinion.

Compare these previous progressive sentiments with that of Associate Justice Joseph Story, who wrote in his 1833 work: “Commentaries on the Constitution,” “The truth is, that, even with the most secure tenure of office, during good behavior, the danger is not, that the judges will be too firm in resisting public opinion, and in defence of private rights or public liberties; but, that they will be ready to yield themselves to the passions, and politics, and prejudices of the day.” Is that not what we just saw happen in Obergefell?

Thomas Jefferson saw the danger during his time, writing to William Jarvis in 1820: “To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”

Besides Obergefell, are there other examples of judicial activism? Lists, long ones, are not hard to find. You’ll find us discussing these cases and more tomorrow morning on “We The People, The Constitution Matters” (7am EDT,

www.1180wfyl.com).

The Heritage Foundation lists these cases (and others) as activist:

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), in which

Justice William O. Douglas, in one of the most famous of judicial DIY projects, constructed a right to privacy from bits and pieces of vague privacy inferences salvaged from “emanations from penumbras” of the Constitution.

Roe v. Wade (1973), building on the “right” of privacy constructed in Griswold, the Court then further defined that “right” to encompass the murder of unborn babies, with few restrictions, striking down numerous state laws.

Lawrence v. Texas (2003), building once again on Griswold, the Court decided that the by now very useful “right” of privacy should be extended even further to sodomy — that states would no longer be allowed to decide whether certain sexual acts were immoral and restrictable. Another dose of “social policy.”

Kelo v. City of New London, Conn (2005). In Kelo, the Court took the plain language of the 5th Amendment and contorted it beyond recognition. The Amendment’s final clause requires that private property taken under eminent domain be only taken “for public use.” Historically, this has meant taking property to build roads and stadiums, install utility lines and other public features which benefit all a locale’s citizens. Not so, said the Court. The City of New London was allowed to take private property and give it to a private corporation (Pfizer Corporation) for the purpose of their building a new private manufacturing plant (reasoning that this would increase the city’s tax base, boost revenues, and thus benefit, well, whoever the city spent the money on). Ironically, Pfizer pulled out of the deal after all the necessary homes were razed and the ground sits vacant to this day. The finding in Kelo encouraged more than one state to pass legislation or

Constitutional amendments protecting private property from just such predations exhibited in Connecticut.

Perhaps the “poster child” of terrible Commerce Clause cases, but also a perfect example of judicial activism since it contorted the clause’s clear wording, is

Wickard v. Filburn. Old Farmer Filburn wanted nothing more than to grow some wheat for his own animals’ consumption; but doing so would exceed his planting allotment. “ If we let you do that,” said the Court (in effect), “you’ll not have to purchase that wheat on the open market, which will affect the interstate market in wheat, which Congress has complete control of under the Commerce Clause.” See the iron-clad legal reasoning? Neither do most people. Wickard was the final nail in the Commerce Clause coffin, and essentially gave Congress (and by extension, the Executive) the power to regulate nearly any business activity. Wickard v. Filburn is the “butterfly effect” applied to the Commerce Clause.

There are many, many more examples and you can study them on several websites. Let’s turn our attention to remedies. What can “We The People” do in the face of judicial activism? We’ll examine six avenues for redress:

Congressional or state legislative or amendment action. We today have several Constitutional Amendments (11th, 13th, 16th, 26th) due to Supreme Court decisions. In some cases the precipitating action was a SCOTUS decision declaring a piece of legislation passed by the Congress to be unconstitutional (16th and 26th Amendments), and sometimes it was merely the implications of a decision. In

Chisholm v. Georgia the Court declared that citizens could sue sovereign states. The Congress replied: “We don’t think that should be so,” and they dutifully passed and got ratified an Amendment putting their view into effect. The 13th Amendment was at least in part the result of the Court’s horrendous Dred Scott decision. In the wake of the Dred Scott decision, many

northern state legislatures scrambled to pass legislation nullifying or muting the effects of the decision.

Jurisdiction stripping: Article 3 Section 2 provides Congress the power to remove any subject area from the Court’s jurisdiction. This was most famously proved in

Ex Parte McCardle when the Supreme Court shut down a case “in mid-stream,” i.e., after oral arguments had been heard but before an opinion had been published. This power has been used often by the Congress but is still not widely understood in that body. In 1996, Congress successfully stripped the federal courts of jurisdiction to review certain INS decisions. Understand also: for Congress to exert this power, a piece of legislation so stating must be passed and signed by the President, which adds another layer of partisanship to the process. Jurisdiction stripping must also be used “judiciously.” If the Congress tomorrow removed the topic of abortion, for instance, from the Court’s jurisdiction, some say that would prevent Roe V. Wade from ever being reversed, or even reviewed. You should converse with your Senators and Representative to ensure they understand jurisdiction stripping.

Impeachment or Criminal prosecution of judges: To date, sixteen federal officials have been successfully impeached by the House of Representatives. These include two presidents, a cabinet member, a senator, a Justice of the Supreme Court, and thirteen federal judges. Of those, the Senate has convicted and removed seven, all of them judges. District Court Judge John Pickering of the District of New Hampshire was the first impeached official actually convicted and removed from office. He was found guilty of drunkenness and unlawful rulings. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase is the only U.S. Supreme Court Justice to have been impeached (he was acquitted, much to Jefferson’s disappointment). In 1981, Alcee Hastings, sitting as a U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of Florida, was impeached and removed from the bench (convicted of accepting a $150,000 bribe in exchange for a defendant’s lenient sentence). Once off the bench, he ran for office and the good citizens of Florida’s 23rd District amazingly sent him to Congress as their Representative!

Presidential refusal to enforce: In a statement that is probably apocryphal, President Andrew Jackson is claimed to have said: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” The decision,

Worcester v. Georgia (1832) required nothing of Jackson, so it is unlikely he said this, but it points to another remedy. The Congress or the President can decide not to give effect to a Supreme Court decision. This of course would create a Constitutional “crisis” and place things in a state of tension. But as Hamilton points out in Federalist 78: the reason he calls the Judiciary the “least dangerous branch” (boy, was he wrong!) is because“It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.” This comports with Jefferson’s opinion that “The Constitution… meant that its coordinate branches should be checks on each other. But the opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action but for the Legislature and Executive also in their spheres, would make the Judiciary a despotic branch.”

[2] In other words: the Congress and President are to act as a check on an activist Judiciary.

Presidential pardon: The President’s pardon power, found in Article 2, Section 2, Clause 1, gives the President the ability to demonstrate that he believes a court acted improperly. Immediately upon taking office in 1801, President Thomas Jefferson pardoned everyone jailed under the onerous

Sedition Act of 1798 (which had given rise to the doctrine of nullification) and even went so far as to return their fines.

Nullification: We discussed this last week on “The Constitution Matters” (you can download the podcast from WFYL’s website). The states and/or the people are free to (and should, according to the venerable Sir William Blackstone) ignore a judicial ruling as null and void if it contravenes natural or revealed law (like the definition of marriage?). A final remedy would be jury nullification, which was used to great effect in response to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and in the aftermath of prohibition (Volstead Act). In both cases juries (Northern juries, obviously, in the case of the Fugitive Slave Act) routinely refused to render guilty verdicts, even in the face of overwhelming evidence of guilt. This action rendered the acts essentially null and void in those jurisdictions.

There are probably other remedies that can be sought in the face of judicial activism. But in the end, what gives a judicial opinion legitimacy (for that is simply what it is: an opinion) is the reaction of the people. A Supreme Court opinion is not the law of the land unless we give it that status.

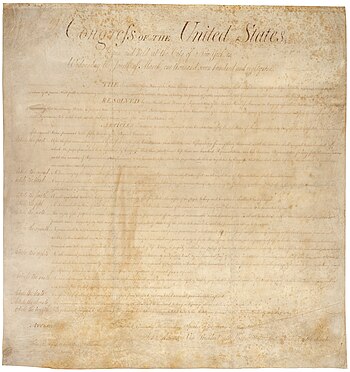

The Constitution does not begin with “We the Judges,” “We the Congress” or with “ I the President.” As I tell all my classes, it is the peoples’ document (with all due respect to those who hold it to be a compact of the states) and “We the People” need to take individual ownership of it. We need to actively work with our representatives in Congress to “put right” terrible Court decisions, and there are many ways to do so. There have been many terrible Supreme Court decisions over the years and Obergefell, I fear, is not the last of them.

Join us tomorrow morning, 7am, on WFYL (Listen Live at

www.1180wfyl.com) to hear your trusty commentators, joined by special guest, Dr. Herb Titus, Founding Dean of the Regent University Law School, as we discuss: “Judicial Activism.”

“Constitutional Corner” is a project of the Constitution Leadership Initiative, Inc. To unsubscribe from future mailings by Constitution Leadership Initiative,

click here[1] Obergefell vs. Hodges, 576 U. S. ____ (2015)

[2] Letter to Abigail Adams, 1804.